I need to start by saying, I love bike trails. About a decade ago, I took up with some people who were doing a weekly casual bike ride they called “Bicycle Beer Time”: ride the Border-to-Border trail from Ann Arbor to Ypsilanti, have a beer and some snacks at Corner Brewery, then ride back home. Before that, I was not much of a bike person, but the ride sounded fun, the people seemed cool, and - critically - the route was easy, safe, and comfortable.

It turned out to be a gateway to much bigger things. It was with this same group of people that I rode on my first multi-day bike tour, a week long ride from Ann Arbor to Traverse City. (We’ve done similar adventures almost every year since then, all over the US and even in Europe). I became a dedicated bike commuter. It’s through bikes that I met and continue to meet some of my favorite people in the world.

So, it’s not an exaggeration to say that the B2B trail changed my life.

|

| The author on the B2B trail, port-ing a pie to a pedal-powered picnic. (Photo credit: Bike-In) |

Knowing that, you’d probably think I’d be in favor of more bike trails - and generally speaking, I am. Indeed, when I first started hearing about the “Allen Creek Greenway” project that has since become The Treeline, I thought it sounded great, though I didn’t really dig very far into the details. This all changed when, in mid-2017, the city released its Framework Plan (which was then revised into the Treeline Master Plan and formally adopted by City Council later that year). As I read further and further into this document, my feelings shifted from excitement to incredulity and even a bit of anger: the price tag and proposed design seemed… preposterous; the plan was completely out-of-scale with what would make sense for Ann Arbor.

Even so, for a long time I’ve hesitated to speak out publicly against The Treeline, because as an advocate for safe bike infrastructure, I’ve become conditioned to take whatever I can get. Opposing a project simply because it’s an expensive and suboptimal design is a hard stance to take when the alternative may well be a big pile of nothing. However, it’s become increasingly clear that The Treeline is worse than that; it threatens some of the most critical work our community is undertaking to address the crises of our time - housing affordability, climate change, and - counterintuitively - bike and pedestrian safety. My concerns fall into four key areas:

- It began as, and continues to be, a means to reject development of badly-needed housing

- Its design represents an outmoded, car-centric way of thinking

- The cost - and opportunity cost - is massive

- It does not address non-motorized mobility in underserved areas of our community

Before I go any further, I should point out that these criticisms apply to the current advocacy efforts around The Treeline (e.g. from the Treeline Conservancy, the private nonprofit set up to pursue implementation of the trail), and to the Treeline Master Plan. There is certainly some value, however, in the core idea of a north-south "urban trail" through Ann Arbor. I believe that by eliminating expensive elevated structures and re-envisioning The Treeline as a ground-level and substantially on-street corridor, it can be salvaged into a much simpler, less expensive, and ultimately more useful amenity.

The Treeline vs Affordable Housing

It began, as things so often do in Ann Arbor, with a plan to build housing on some city-owned parking lots. In 2005, the Downtown Development Authority (DDA) proposed what was known as the “three site plan”, which would have built mixed-use high-rise buildings at Ashley & William and First & Washington, and a new parking deck (along with a public park larger than Liberty Plaza) at First & William. While A2’s housing affordability and availability in the mid-2000s hadn’t reached today’s crisis levels, it was already becoming a serious problem. But as the venerable Richard Murphy wrote in an opinion piece at the time:

… On the other side are the Friends of the Ann Arbor Greenway, a slogan-toting band of nearby homeowners who have decided that this looks like an excellent opportunity to score themselves some pork. Sorry, “park.” The Friends are demanding that no parking structure be built and that the site be devoted entirely to parkland. They’ve dismissed the DDA’s park as a “token park,” demanding a “full-scale” greenway instead — a difference of perhaps an acre... They seem to have some issues with money: Anybody who supports the DDA’s plan is “in the pockets of the big developers” (my kickbacks must have been lost in the mail), and they studiously avoid talking about where the money is going to come from for their version of the park, let alone all of the other sitework needed. They’re deceptive — simplifying the issues to “parks, not parking structures!” — and they’re just plain mean, openly booing a student who said at a city council meeting that the DDA’s plan would benefit the whole city, while the Friends vision would only benefit their neighborhood…

If you’ve wandered around the west end of Downtown recently, you can probably tell which side “prevailed”: the parking lots at First & William and Ashley & William are still, 15 years later, parking lots. (The First & Washington site was eventually redeveloped into today’s Ann Arbor City Club Apartments). Indeed, City Council failed to approve the three-site plan, and instead ordered the creation of a task force to study the greenway proposal, which began the long, drawn-out, and expensive process that eventually led to the 2017 Treeline Master Plan.

At this point you might be thinking this is all ancient history, that it’s water under the bridge. I might agree, except that it’s all happening again. Faced with an extreme housing affordability crisis, the city has embarked on a process to leverage city-owned sites to build affordable housing, including the remaining two undeveloped sites from the original “three site plan”, as well as two others implicated in the Treeline project: 415 W. Washington and 721 N. Main. Time after time, The Treeline has been held up as a reason to delay or block progress on these sites:

- At the March 18, 2019 City Council meeting, CM Ackerman brought forward a resolution directing the city to explore developing affordable housing on 721 N. Main. Prior to the meeting, Joe O’Neal (The then-Chair of the Treeline Conservancy and one of the principal longtime supporters of the project) sent an email to City Council asking that the resolution be delayed and stating that he believed it was “not in keeping with” the “business plan” being developed by his organization. It’s important to note that - per the City Administrator’s comments during the meeting - the city had been working in good faith with the Treeline Conservancy to implement a trail segment on that site, the final text of the resolution explicitly called for that, and the “business plan” mentioned by Mr. O’Neal had not been agreed to or adopted by the city at that time.

- At the April 20, 2020 City Council meeting, staff brought forward a resolution to initiate a “pre-entitlement” effort to develop housing on 415 W. Washington (as a follow-up to prior Council direction to explore ways to leverage the site for affordable housing). Nan Plummer, the Executive Director of the Treeline Conservancy, called in for public comment, and asked that the resolution be tabled because it “did not consider all alternatives” and that “the full potential of the Treeline and other desirable uses could be automatically precluded”. These comments were delivered in spite of the fact that the resolution explicitly called for space to be set aside for a potential Treeline greenway on the site.

- In a December, 2021 article on the 415 W. Washington project, nearby residents interviewed by The Ann Arbor Observer mentioned the potential Treeline trail as one of a litany of reasons why the housing-development proposal should be shelved: “... Ann Colvin says it’s not the low-income aspect of the project that bothers the neighbors, but the height. Colvin would rather see the site used as an anchor park for the Treeline…”

These arguments are the same as they were 15 years ago - it’s not enough that the city is setting aside space for the trail in all these plans; people calling themselves supporters of the Treeline are once again demanding that the sites be used as “parks” in their entirety, and using every tactic at their disposal to delay and diminish potential affordable housing gains in the city. To be clear, I’m not claiming to know what the leaders of the Treeline Conservancy truly intend; they have made comments supporting affordable housing, but also - as noted above - taken some steps that would seem consistent with a goal of rejecting development on these sites. Yet even if rejecting development is not the Conservancy’s explicit goal, others in the community are quite overtly utilizing The Treeline for such a rhetorical purpose.

Given the existing example of what’s happened with the First & William parking lot, it’s hard to believe that these advocates actually even care about parks. Ironically, had the DDA developed its 3-site plan, a good portion of that lot would already be a park! Instead, it remains covered in asphalt. This offers us a good template of what will likely happen on these blighted and underutilized sites if we reject the latest development proposals: absolutely nothing. (Astute readers might note many parallels to the saga of a different controversial parking lot in downtown A2.)

This is a shame, because - at least in the case of 721 N. Main - I do believe a trail connection between Summit and Felch would be valuable, and wholly compatible with building housing on that site. On 415 W. Washington, however, I have a different view - the trail simply does not need to exist in that location. Why, you ask? Well…

Car-Centric Thinking

|

| Le Corbusier's "utopian" vision |

In the 1920s and 1930s, the modernist movement - led in particular by an architect and planner known as Le Corbusier - had a radical new vision for city design. One fundamental through-line in their approach was separation of uses. Buildings would be divided into distinct residential and commercial areas. Cars and pedestrians would be separated onto different vertical levels. Giant thoroughfares would be plowed through the hearts of cities, allowing cars to flow unimpeded at high speeds. These ideas had a profound impact on how cities developed around the world in the latter half of the 20th century. They were also - as we’ve learned through decades of urban decline and destruction - badly wrong. It’s now widely understood that cities are at their most vibrant and successful when they permit a mix of uses and activities to coexist, and when they’re designed to serve the needs of people, not to simply allow cars to move at high speeds.

So this is in large part why most “pedestrian infrastructure” is actually for drivers. Pedestrian bridges are often inconvenient to use (they require traversing more horizontal and vertical distance), and they essentially represent a surrender of the ground level to exclusive use by drivers. Even if we keep our sidewalks and ground-level crosswalks intact, the presence of a bridge dilutes street-level activity and signals that people simply do not belong there.

|

| It's not pretty, but this is what good "pedestrian infrastructure" actually looks like. |

This is not to say that pedestrian bridges are never a good idea. My favorite bridge in Ann Arbor is the lonely, random pedestrian bridge crossing I-94 between the Bryant neighborhood and Mary Beth Doyle park. With an interstate highway, my concerns about surrendering the ground level to exclusive use by drivers are moot; that surrender was already made and is total. Pedestrian bridges can mitigate the harm done to our communities and restore connectivity that was broken when we built these impenetrable barriers.

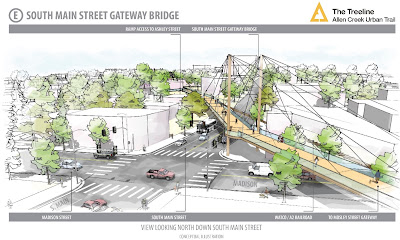

Downtown Ann Arbor is, however, a very different place from I-94, yet the Treeline Master Plan calls for no fewer than 5 bridges (and one tunnel). We should not do this. We should not surrender the ground level of our urban core to use by cars. We should, rather, re-design our streets to be safe, comfortable, and vibrant for all users. In fact, the DDA has already shown us the way by - for example - converting First St. from a wide, one-way racetrack for cars to a lovely street that comfortably accommodates all users with two-way car traffic, a curb-separated cycle track, and beautifully designed sidewalks. This is what a vibrant, safe downtown street looks like. We should do more of this.

|

| First St. in late 2021 (Photo credit: A2 DDA) |

In fact, because the First St. bikeway already exists, the portions of The Treeline that would run roughly parallel to it - the stretch between Kingsley and William, which includes 3 of the proposed bridges and a tunnel under the railroad - would simply be redundant. There is no need to build a trail there. There may be other reasons why it still makes sense to leave portions of the 415 W. Washington site as "green space", but the trail certainly offers no legitimate justification to delay or reject housing on that site.

In addition to being a fundamentally better approach to urban placemaking, there’s another advantage in using ground-level / on-street infrastructure to implement an urban trail: it’s much, much less expensive.

The Price Tag

The 2017 Framework Plan offered a preliminary estimate that the project would cost around $55 million. At a total length of 2.75 miles, this would average out to an utterly exorbitant $20 million per mile. It’s also likely that this was a severe underestimate. It explicitly excluded a litany of items - property acquisition, utility modifications, environmental remediation, on-going maintenance costs, etc. Between those exclusions and a general expectation that preliminary estimates tend to fall short, a City Council member at the time privately suggested to me that rounding it up to an even $100 million might be more realistic. Still, for the purposes of this discussion, let’s take that $20M / mile number at face value and compare that to the costs of some other approaches.

The First St. bikeway was built as part of a much larger project to rehab underground infrastructure and completely reconstruct the street. In 2018, DDA Executive Director Susan Pollay stated that the costs specifically attributable to the bikeway were around $700,000 (out of a total project cost closer to $13 million). At a length of 0.5 miles, this works out to around $1.4M / mile, less than one tenth of the projected Treeline costs.

If First St. offers a lower-bound for the price of a high-quality, curb-separated bikeway in Ann Arbor, the recently-completed Division St. bikeway might provide an upper bound. Unlike on First St, this project was not part of a larger reconstruction effort, and so the whole cost can be attributed specifically to installation of the bikeway itself. This project cost was estimated at around $1.9 million. At a length of around 0.6 miles, this works out to about $3.2M / mile - considerably more than the First St. estimate, but still less than a fifth of the projected cost for The Treeline.

Imagine if we had $55 million to spend on bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure anywhere in the city. That kind of money could go really far in implementing and improving on-street and ground-level sidewalks, bike paths, and trails. Ann Arbor’s new comprehensive transportation plan calls for an ambitious, citywide network of “all ages and abilities” bikeways; only a small fraction of this proposed network currently exists. We should invest in building out as much of this network as we can, as quickly as we can, rather than concentrating funds on a short and substantially redundant project.

Now, the reality is that we don’t have $55 million to spend on whatever we want. The Treeline Conservancy is making significant efforts at private fundraising, which could arguably bring money to that project that our city would otherwise not receive at all. However, I still have two concerns about this:

- Eventually, inevitably, there will be some sort of request for the city to provide funding. In other public recreation projects, the city has shown some willingness to throw in public funds to “match” private fundraising (e.g. to construct the Ann Arbor Skatepark). This has generally been a positive approach, but I do not believe it would be in the case of a project as misguided as the Treeline.

- Even private philanthropy can sometimes be a zero-sum game. Since 2018, the Ralph C. Wilson Foundation has been one of the most prolific funders of hiking/biking trails in Southeast Michigan; their contributions have enabled construction of key links in state-wide trail networks. However, even for such a well-endowed organization, funds are not unlimited. If they - or any similar organization - were to award a grant to the Treeline, that grant would likely come at the expense of some project somewhere else.

Non-Motorized Transportation Gaps

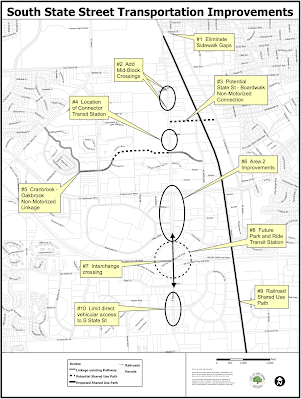

One great irony of the Treeline Master Plan is that earlier visions for the trail would actually have provided some benefit to areas of our community with significant non-motorized mobility challenges - specifically, the corridor south of Stadium, between Main St. and S. Industrial. As one example, the South State Street Corridor Plan from 2013 contemplated a non-motorized pathway along the railroad tracks extending under I-94 and all the way to the city limits at Ellsworth, as well as some potential east-west connections between Main and State, and between State and S. Industrial.

These connections would represent a massive improvement to non-motorized mobility in this area of town. Between the railroad tracks and the University of Michigan’s closed-off athletic campus, getting around (or through) this part of town is currently quite challenging. Bicyclists or pedestrians heading east or west must travel all the way north to Stadium or south to Eisenhower (neither of which has particularly comfortable or safe bike lanes). There are better options for north/south travel - e.g. the new bike lanes on S. Industrial - but none of them would count as a low-stress / all-ages-and-abilities route.

All of this could have been part of The Treeline master plan, yet the decision was somehow made to exclude this from the plan and leave it in limbo as potential future work. The trail contemplated by the master plan ends at State and Stimson, right where the real, serious mobility challenges begin.

There’s another, perhaps more fundamental issue at play here - the subtle but important distinction between recreation and non-motorized transportation goals in biking/walking projects. Generally speaking, projects designed for non-motorized transportation can also serve a recreational purpose, but the reverse is often not true. In addition to being safe and comfortable, transportation routes must be direct, convenient, and available year-round - which is to say, plowed in the winter. (Even my beloved B2B trail mostly fails to meet these criteria, which is why I’m adamant that a Packard Bikeway should be made one of the top non-motorized transportation priorities at the county level).

In its currently-proposed form, the Treeline seems to be entirely a recreation-oriented project. It would duplicate existing routes, establish very few useful new connections, and potentially risk making street life in downtown Ann Arbor worse for anybody not in a car. Meanwhile, what Ann Arbor actually needs - and quite urgently - is to add and improve non-motorized transportation routes. After all, the city has declared a climate emergency and established a goal to reduce vehicle miles traveled by 50%.

Let’s build a Treeline trail that actually works for Ann Arbor

These issues are solvable. As I said at the top, there is certainly some value in the core idea of a contiguous north-south bikeway through Ann Arbor - but instead of building massively expensive bridges and using the trail as an excuse to block badly needed housing construction, we should instead build the trail using ground-level and (substantially) on-street connections. We should also extend it further south, into areas of Ann Arbor that badly need more and better non-motorized transportation connections.

The existing planning documents for The Treeline even contemplate these ideas. The recently-released Phase 1 Alignment Study for the northernmost area includes (but does not recommend) an “on-grade option” that would leverage the recently-completed Argo tunnel and on-street connections to traverse between the B2B trail and 721 N. Main.

The 2017 Master Plan also discussed - but ultimately dismissed - on-street alternatives using First St. and/or Ashley St.

Here’s my rough proposal. While similar to the 2017 Master Plan’s “First Street Option”, it does include a few more off-street trail segments and other modifications to match some features that were completed in the intervening years:

- Implement the “on-grade option” from the alignment study to connect from the existing Argo tunnel trail, through Wheeler Park, to 721 N. Main. There are a few aspects of this that are admittedly not ideal. First, the Argo Trail would be an indirect route; it forces people to go significantly out of their way to the east. Efforts should be made to convince adjacent property owners to grant an easement allowing a more direct westbound connection.

Second, the Summit/Main crossing would need safety improvements, and the best ways to achieve this would require performing a 4-to-3 lane road diet on N. Main. Having done that, it could then be feasible to add additional treatments like refuge islands, curb extensions, etc. Unfortunately, N. Main is currently under the jurisdiction of the Michigan Department of Transportation, which is generally more hostile to such changes than the City of Ann Arbor would be. News recently broke that the city is beginning a process to consider taking over jurisdiction of this and other “State trunklines”, which could be one potential path forward. - Construct a trail segment through 721 N. Main and use the existing easement beside Kingsley Condos to connect the trail to First St. This segment would be consistent with the Treeline Master Plan’s preferred alignment.

- Re-designate the First St. bikeway AS the Treeline!

- Continue the bikeway (past its current terminus) south on First and east across Madison. While I generally support the city’s use of advisory bike lanes on neighborhood streets, I do not believe they would be adequate for a signature urban trail. These additional blocks of S. First and Madison should be upgraded to include a fully protected bikeway.

This segment should also include safety improvements for the Madison / Main crossing. For this to be successful, we will need to ensure that the current “pilot project” road diet on S. Main is made permanent; in addition to the major safety improvements this project has already produced, it will (again) enable further work - e.g. curb extensions, refuge islands, etc. - that could significantly upgrade the experience of crossing this road. - Implement the rest of the Treeline Master Plan, heading southeast from Madison, largely as-is. It would be a worthwhile effort to re-engage with the University to see if e.g. their purchase of the Fingerle site may have changed their plans in this area and made them more amenable to off-street pathways along the railroad corridor.

- Construct the pathways contemplated by the South State Street Corridor Plan, and extend the trail under I-94 to the south side city limits.

Very well thought out. A south side connector along the train tracks seems almost organic. As a kid (circa 1998) we would use these tracks to connect from Georgetown to downtown by foot or on bike.

ReplyDeleteNicely written and well explained. I can't claim to be clear on the details. But yes, the current plan seems at best overpriced and at worst just the wrong thing.

ReplyDeleteGreat discussion. On a pragmatic tack, do you know if there is a plan to connect the Division St bikeway to the Medical Center (our largest employer)? That seems to be a key missing link (right now there are not a lot of great, safe routes) to boosting commuter bike traffic.

ReplyDeleteThis is part of my concern. Did you know the bike boulevards aren't recommended by NACTO in the places we're putting them? If you go to our sister city, Tubingen, and a lot of other northern European cities that are great for biking (yes, yes, the Netherlands is different, but it's also flat as a pancake), they don't need to spend so much money with these kind of trails. People bike in most places, with fewer of these expensive trails. And we need people biking everywhere.

ReplyDeleteThe problem with bike infrastructure in Ann Arbor has always been that we put in the crappiest bike lanes we can - usually absolute minimum AASHTO bike lanes, when even AASHTO (not to mention FHWA and NACTO) recommend better. Almost inevitably they're next to quite wide road lanes, even when in many of those situations the Green Book says we can go narrower with the road lanes.

Then we do nothing at all to maintain those bike lanes. They're full of gravel, potholes, water connection lousy repairs, etc. My favorite example was the large blob of concrete dumped in the Division bike lane by Catherine, which was reported on A2Fixit within a week of it appearing, and the city didn't get around to removing for like eight months.

And, most importantly, we ignore the large volumes of *always* speeding hyper aggressive SE Michigan motorists. How aggressive are they? Most traffic calming guides say that bike lanes, particularly with cyclists in them, are a form of traffic calming. That's because motorists are supposed to see a bike lane, and particularly a cyclist, and slow down some. Which *never* happens in Ann Arbor, because we're full of out-of-town hyper aggressive motorists.

The good thing about the bike boulevards is that they take away a lane, forcing more congestion, which forces the motorists to slow down some. But, on the other hand, I watched a motorist last week drive down the Division boulevard from the Firestone entrance drive to Huron, to make a (now) illegal right-on-red there. Did I mention aggressive driving?

Once upon a time, we were looking into revising our non-motorized plan. I was on the consultant selection committee. One of the bidders was a team of Cambridge Associates and Charles Komanoff, of NYC's Transportation Alternatives. I'll never forget the conversation. I don't remember the specific question we posed, but Mr Komanoff said that "We probably need a lot more traffic calming." I responded with a chuckle, and said, "Well, we'd probably need traffic calming all over town." He replied, in utter seriousness, "Yes! Many American cities really could use traffic calming nearly everywhere." We couldn't imagine it, and the local consultant we'd worked with before got the job.

Then I went to Europe and biked around there. And, wow, they really had traffic calming pretty much everywhere. And it works. We could put in an awful lot of traffic calming for $55 million, and make the entire city safer for biking and walking, as well as make more progress on both Vision Zero and A2Zero. Instead we'll put in a few very expensive boulevards and trails, and the same hyper-aggressive out-of-town motorists will get twice as mad at those of us biking to actual places, because we're supposed to get off "their" roads and use the path.

As I see it, having State & Stimson as a destination only made sense when using the railroad right-of-way was an option. It's not much of a destination itself, it's just where the tracks went. Now that the railroad said forgetaboutit, well, forget State & Stimson as a specially marked route ending.

ReplyDeleteHa! I bike to State/Stimson daily, because that's where my gym is. Also By the Pound, since they got displaced from S. Main. Admittedly, that's just me. But I do see lots of cyclists on State, and continuing south of Stimson. We desperately need a bike corridor on State. And for much of State it would be easy to do, plenty of ROW.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

Delete